Stromboli

This is why you don’t read the preface, or worse, the introduction, first. It’s useful if you’re a student trying to grasp on immediately to what the conventional wisdom is about something, trying to pass a course. Dig in to what they expect you to know. On one level, so sensible. But for making up your own dangerous mind, not so good.

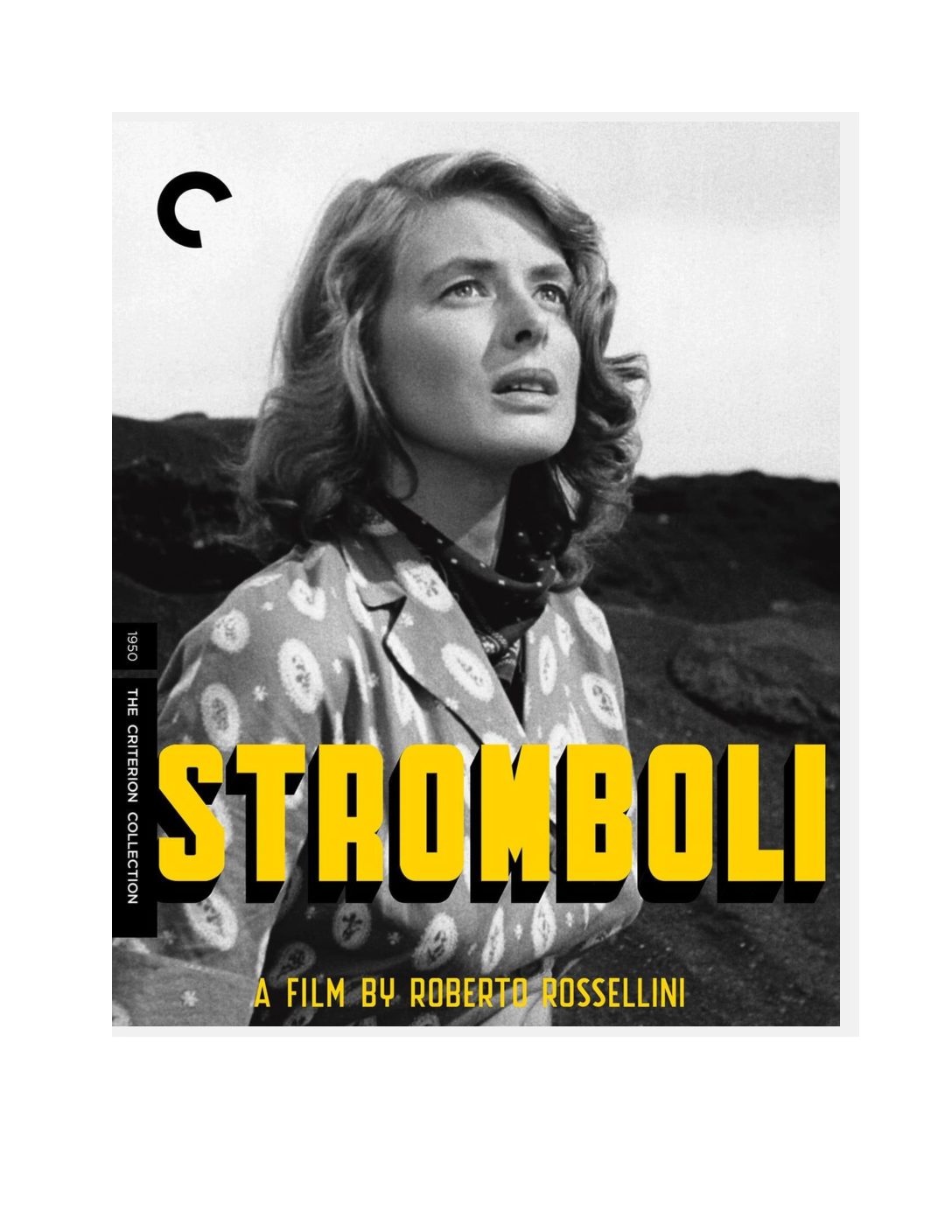

Stromboli, this movie, had been on my list of things to watch. I don’t always like movies – they are either too intrusively emotionally, or too stupid. Watch a movie, dream about it all night. But since I had watched For Whom the Bell Tolls on a Gary Cooper/Ernest Hemingway search collision, and spent hours crying, for the first time in weeks? months? years? I had emerged wondering why I hadn’t realized before that Ingrid Bergman was a goddess. Then I was determined to watch her films. But had avoided the movement of thought to action, in the usual way. Indoors, as we are.

Then one night, there Stromboli was, so siren red and loud with its volcanic cover, standing out on my list on the screen. I’m here, there’s the movie, yes I will manage with the IMDB channel ads. A mere button pressed, as you do these days. But I stayed put and I watched it.

Afterwards, when I stopped drifting around in a fog, wondering what it felt like to climb those steps to the small dwelling, to touch her hand as she painted the wall, the glory of her face, happy and simple in expression, the art of making a home, of making anything, to feel the lava rock shards under your feet, the heat as you leave everything behind, to know to camaraderie of loss, the longing of women, to reach out to touch someone through a barbed wire fence, to have applications refused for nothing, to wonder how long those displaced persons camps had existed for after the end of the war, to face the time that distance meant, the endless sea, Homeric with its insistent choice of loss, to watch the primitive struggle of wanton death, the blood and the wounds, the soon-to-be corpses thrown on the pile – men or animal?, her switch from innocent to wanton, all intentional, then rejecting it, false, hopeless, was it the ease of destroying morality or the mere ease that ended it – then – then – then I wanted to read about the making of the film.

What must the reviews be like? This view of a world that no longer exists? I imagined what the current place must look like – would it be all villas and yachts? Certainly it wouldn’t be the peasant, hardscrabble life depicted on the screen. And the tale beneath it all of all the displaced persons of the second world war. We imagine everyone was fine or dead, but the simplicity of that idea is immediately erased from the first minutes of the film. Lives were destroyed – yet they still had to live.

I had seen the film.

So the reviews must be luminous, as Bergman was. The contrast between her shimmering presence, radiating glorious hope and dark awareness in equal measures.

But no. Europe appreciated it. But Americans were shocked and appalled. She had a child out of wedlock. She was blacklisted as thoroughly as were the Jewish screenwriters who were called communists. Oh, we’ve been a stupid country for a long time. But aside from the political and social ostracizing Bergman experienced – ironically, as that is one of the themes of the film – there is another reason why it wasn’t successful.

She is the hero. The heroine. The “man,” the subject, fighting with the demons, determined to wrestle her own path from the gods. She understood her worth and was not waiting either to be acknowledged or saved. She confronts every lie, every myth of womanhood, and struggles with what most heroes do – the consciousness of pain, of art, of isolation – while adding to the mix her awareness of sin and cruelty, neglect and fragility. Women were not supposed pushing at the side of Sisyphus – they were supposed to be his mistress, his friend, his maid, his cook, his lover – but never the one struggling themselves.

Yes, they all apologized – even the Senator[1] who denounced her in a fine fit of pique, such as you would expect from Joe College finding his Sorority Queen turning unto you a never before seen image; a drastic shift of gaze, curiosity to desire, acceptance to control, observation to action. The apology came, such as it was, once Bergman had redeemed herself with marriage again, and declarations of motherhood, and the stench of McCarthyism had been aired out somewhat.

As a note to world of today, clearly there is a real problem in Colorado.

But no one talked of the goddess, barefoot and in tears, trapped on the mountaintop, facing down demons of loss and life and self-destruction, still determined to make god listen when men would not.

To make god listen when men would not.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/1972/04/29/archives/ingrid-bergman-gets-apology-for-senate-attack.html